When Nations Stay Away

Sri Lanka’s SCO Absence

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) is one of Asia’s most influential diplomatic forums, bringing together major powers including China, Russia, India, Pakistan, and four Central Asian republics to discuss security, economic cooperation, and regional stability. This year’s summit, held in Tianjin, China from August 31 to September 1, 2025, attracted over 20 world leaders, including Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi making his first visit to China in seven years, and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Yet one notable absence stood out: Sri Lanka’s President Anura Kumara Dissanayake did not attend, despite the country holding “dialogue partner” status in the organization since 2010. While official explanations cited the President’s “crowded presidential schedule,” this absence reflects deeper geopolitical currents as Sri Lanka navigates increasingly complex international waters amid external pressures and competing global alignments.

A Pattern of Strategic Absences

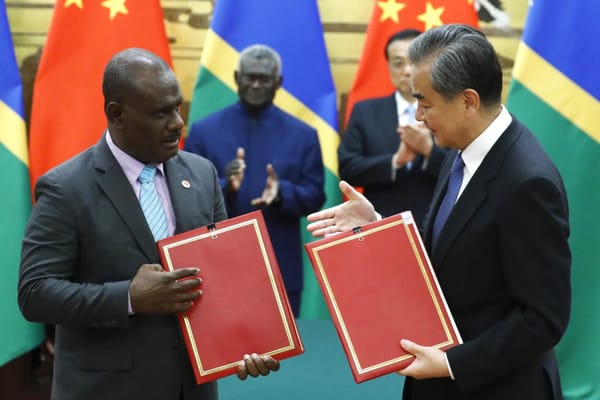

Sri Lanka’s diplomatic challenges extend far beyond the SCO. The island nation’s relationship with BRICS — a major economic bloc comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa that represents about 40% of the global population — reveals a similar pattern. BRICS nations meet annually to coordinate policies on trade, development financing, and reducing dependence on Western-dominated financial institutions.

Sri Lanka applied for the BRICS membership in October 2024 and secured the backing of several foreign ministers. But then it made a critical error at the crucial Kazan summit in Russia. While many other nations gained coveted “partner” status, Sri Lanka sent only its Foreign Secretary rather than a high-level delegation. This decision proved costly as Sri Lanka’s application was rejected. Although it got access to the BRICS New Development Bank, which provides infrastructure funding that could aid the country’s ongoing economic recovery.

Global Patterns: When Countries Choose Absence

However, Sri Lanka isn’t the only case. Such behavior reflects broader trends where nations increasingly face difficult choices about international alignment, often resulting in strategic absences from major forums.

Diplomatic boycotts occur even within established blocs. ASEAN has excluded Myanmar from its summits since the military coup in 2021. Myanmar’s absence from six consecutive ASEAN summits severely damaged its regional standing and economic prospects, demonstrating how domestic politics can isolate nations from crucial regional forums. Recent years have also seen increasing absenteeism across Southeast Asia, with Indonesian and Thai leaders missing ASEAN summits for domestic political commitments, reflecting changing diplomatic priorities even among founding members.

In 2024, six EU countries — Sweden, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Finland — boycotted meetings hosted by Hungary over Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s unauthorized visits to Russia and China during wartime. The European Commission itself partially boycotted Hungary’s EU presidency, sending only civil servants rather than commissioners to meetings.

Understanding Sri Lanka’s Motivations

Several factors explain Sri Lanka’s recent diplomatic absences. Reports suggest Sri Lanka declined China’s SCO invitation due to “pressures from an undisclosed foreign mission”. This aligns with smaller nations facing competing demands from major powers, forcing difficult choices about international alignment. Sri Lanka’s ongoing economic crisis also necessitates careful diplomatic balancing. With India providing $4 billion in crisis assistance and China holding significant infrastructure investments through projects like Hambantota Port, the island nation must navigate between competing benefactors without alienating either. It’s also worth noting that President Dissanayake’s National People’s Power government, despite its historically pro-Chinese roots, chose India for his first overseas visit, signaling a deliberate recalibration of regional relationships.

The Broader Regional Recalibration

Sri Lanka’s summit diplomacy reflects fundamental shifts in global alignment. Smaller nations increasingly face pressure to choose sides in great power competition, leading to more cautious and selective international engagement. This creates both risks and opportunities for regional powers like India.

The key lesson for Indian policymakers is moving beyond demanding exclusive relationships toward proving India’s value as a reliable, patient partner willing to support neighbors’ legitimate aspirations for economic development and international engagement.

India’s Neighborhood Challenge and Opportunity

India’s “Neighbourhood First Policy” — launched in 2008 and intensified after 2014 — aims to strengthen ties with immediate neighbors through economic cooperation, infrastructure development, and cultural exchange. However, this policy has faced significant challenges across the Indian Subcontinent, as Chinese Belt and Road Initiative investments create competitive pressures, and has yielded only mixed results.

While India provided crucial assistance during Sri Lanka’s economic crisis, it has found difficulty matching China’s long-term infrastructure commitments. Similar patterns emerge across the region — the Maldives oscillates between India and China with changing governments, while Nepal increasingly looks to China for development projects. Sri Lanka represents both the challenges and opportunities of India’s regional approach. Despite substantial Indian economic assistance, the relationship requires constant recalibration against Chinese influence.

Strategic Implications for India

Sri Lanka’s absence from major multilateral forums creates unique opportunities for India to strengthen bilateral ties. India can accelerate the proposed Economic and Technological Cooperation Agreement, expand digital cooperation through platforms like Aadhaar, and support Sri Lanka’s IMF bailout program while increasing infrastructure investments.

Rather than competing directly with China in infrastructure spending, India can also support Sri Lanka’s eventual BRICS membership through Indian advocacy, facilitate integration into Indian Ocean initiatives, and promote South-South cooperation. President Dissanayake’s guarantee that “Sri Lankan territory would not be used in ways inimical to India’s security” represents a significant diplomatic victory that India can build upon.

Opportunity in Absence

Sri Lanka’s recent absences from international summits, while representing missed opportunities for itself, create new openings for India to rebuild regional influence through a more nuanced approach. Success requires addressing economic needs, security concerns, and political sensitivities across the neighborhood without the competitive pressure that has sometimes characterized India’s regional diplomacy.

Sri Lanka’s current diplomatic recalibration offers India a crucial test case for this evolved neighborhood strategy — one that emphasizes support rather than pressure, patience rather than demands, and mutual benefit rather than zero-sum competition. The results will likely influence India’s approach to regional diplomacy across the Indian Subcontinent for years to come.