De‑Risking and the New Geoeconomics

India’s Tightrope Walk

Today’s global order is being reshaped not only by military alliances or political ideology, but increasingly by the deliberate use of economic tools to secure strategic advantage. The new world is one where shipping lanes, data servers, and semiconductor fabs matter as much as aircraft carriers or missiles. This shift — often described as the age of geoeconomics — can be seen in how major powers are restructuring trade, controlling supply chains, and setting technological standards. For India, this presents both an opportunity and a challenge. On one hand, it gives India a chance to emerge as a trusted alternative in global value chains, but on the other, it also comes with a risk of being squeezed between competing blocs.

From Geopolitics to Geoeconomics

Geoeconomics refers to the use of economic instruments — tariffs, export controls, subsidies, investment rules, infrastructure financing — as means of advancing strategic objectives. Unlike Cold War geopolitics, which was defined largely by military containment, today’s competition is fought through chips, shipping lanes, and digital platforms.

This is not just a theory. The US has imposed sweeping export controls on advanced semiconductors; the EU speaks of “strategic autonomy”; China has been pushing its Belt and Road outreach; India is trying to advance its “Make in India” and digital public goods diplomacy, and so on. The common thread is de-risking: limiting exposure to external shocks, whether from sanctions, pandemics, cyberattacks, or conflict. In practice, this means reorganizing supply chains, designing new financing mechanisms, and protecting critical nodes of the economy.

The United States: Managed Interdependence

The USA’s approach has centered on reshoring critical industries, subsidizing domestic production, and tightening export controls on sensitive technologies. “Friendshoring” — encouraging allies to host production — has become a catchphrase. The logic is not full decoupling from China, but “managed interdependence”: retaining some trade links while ring‑fencing strategic technologies. The CHIPS and Science Act, and subsidies for electric vehicles and renewables, reflect this broader logic.

The European Union: Between Autonomy and Dependence

Europe has been explicit about “de‑risking from China.” The EU’s playbook combines tighter investment screening, diversification of suppliers, and heavy investment in renewables, batteries, and semiconductors. Initiatives such as the European Chips Act are designed to ensure technological sovereignty. However, Europe is also trying to de‑risk from the US in certain domains such as digital standards, data regulation, and defense procurement.

China: Counter‑balancing the West

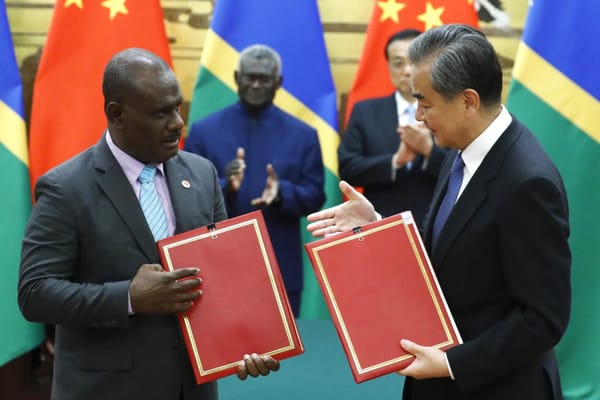

China criticizes Western de-risking as thinly veiled protectionism. Its response has been twofold: doubling down on the Belt and Road to create alternative corridors, and investing in domestic innovation under its “dual circulation” strategy that emphasizes strengthening the domestic economy (“internal circulation”) as the primary driver of growth, while also maintaining and supplementing it with external trade and foreign investment (“external circulation”).

As a result, China remains deeply embedded in global supply chains. Even under multiple shocks, many global industries cannot easily bypass Chinese inputs. From solar panels to pharmaceuticals, China’s role is central. However, this also exposes China to the risk of a collective pushback if multiple states coordinate to diversify away. In addition, it also faces the challenge of retaining foreign investment in a climate of rising suspicion. If Western de-risking accelerates, China may be forced to rely more on domestic consumption and Global South partnerships to sustain growth, which may be one of the reasons why it seems to be warming up its relations with India.

India: Multi-alignment and Capability Building

For India, geoeconomics is both an opportunity and a test. India pursues a strategy of multi-alignment, whereby it engages simultaneously with the US, EU, Russia, and China, for avoiding lock‑in to any single bloc. This geoeconomic strategy relies on multiple tools: industrial initiatives like Make in India and PLI schemes to build manufacturing capacity, digital public infrastructure exports to provide affordable alternatives to Western platforms, and connectivity projects such as Chabahar port to bypass chokepoints. It also employs cultural diplomacy — ranging from Buddhist relic exhibitions to educational exchanges — to foster trust and strengthen the foundations of economic cooperation.

The upside is clear: as Western firms seek to diversify away from China, India is a natural candidate. Reports already suggest sourcing is shifting to “China + many,” with India gaining share. In aerospace and defense, major firms like Airbus are holding meetings in India to explore deeper cooperation. In digital payments, India’s UPI system is being exported to Southeast Asia and Africa, showcasing how digital diplomacy becomes economic leverage.

Constraints and Critiques

Yet challenges remain stark. India still lacks the technological depth to fully substitute for China. Critical sectors — electronics, advanced manufacturing, rare earth processing — remain dependent on imports. Infrastructure bottlenecks, regulatory uncertainty, and cost competitiveness further limit India’s capacity to absorb large relocations of global supply chains.

Moreover, India risks being caught in external disputes. The recent US proposal of a steep visa fee on H‑1B workers — directly impacting Indian IT firms — illustrates how quickly policy shocks can undermine a sector. Trade frictions in the EU over data protection and environmental standards present another layer of complexity. In such cases, India’s dependence on external markets becomes a vulnerability rather than an asset.

Domestic capacity is also uneven. While pharmaceuticals and services are global strengths, manufacturing scale remains elusive. India’s share of global electronics exports is still marginal, and supply chain integration lags behind Vietnam or Mexico in many cases. Without bold reforms in logistics, taxation, and labor, India may struggle to convert external goodwill into concrete industrial relocation.

The Global Trade‑Offs

The debate over de‑risking highlights difficult trade‑offs. Overly aggressive reshoring could fragment the global economy, shrink trade, and raise costs. On the other hand, ignoring risks leaves states exposed to coercion and shocks. Most likely, the outcome will be partial diversification rather than full decoupling: supply chains will be re-wired, not dismantled.

For India, this means opportunity in specific sectors — such as pharma, renewables, digital platforms — without expecting a wholesale shift of manufacturing away from China. The test lies in whether India can provide scale, reliability, and a stable regulatory environment to convince global investors. Much will also depend on India’s ability to integrate with other emerging economies, offering not just itself but also regional networks as alternatives.

The global economy is entering a period where redundancy, resilience, and regionalization matter more than pure efficiency. This has implications for inflation, growth, and employment worldwide. For developing countries like India, the challenge is to capture the upside of new investments without being trapped by higher costs and geopolitical disputes.