Central Asia’s Middle-Power Turn

Why It Matters for India’s Eurasian Strategy

In April this year, the European Union hosted the first-ever EU–Central Asia Leaders’ Summit between leaders of the EU and the five countries of Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan) in Samarkand, pledging a €13.2 billion investment under its Global Gateway initiative. Since then, more than €10 billion in investment windows are now being mobilized, spanning infrastructure, logistics, energy, and digital connectivity. A roadmap for critical minerals has been formally endorsed, with follow-up implementation tracks in progress.

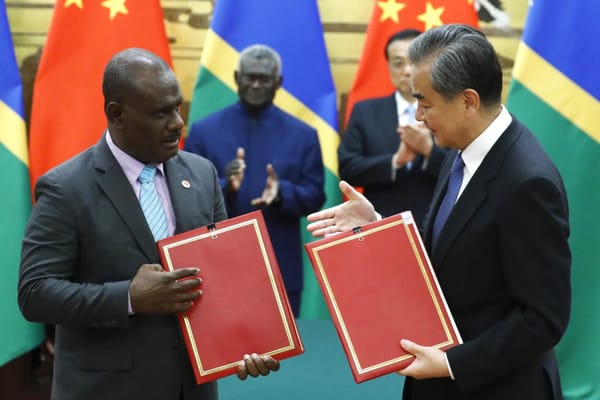

In a show of parallel diplomacy, China also hosted its own high-profile China–Central Asia summit in Astana in June, offering an alternative template for engagement. These overlapping moves underscore a major shift in regional geopolitics: Central Asia is no longer a passive arena for great-power rivalry but an increasingly proactive group of middle-power actors.

What “Middle Power” Means in Central Asia

Middle powers are defined less by their size or military might and more by their ability to influence regional or global outcomes through soft power, coalition-building, norm-setting, and diplomatic brokerage.

In the Central Asian context, Kazakhstan most closely fits this model, as the region’s economic powerhouse and most mature diplomatic actor. However, it’s walking a tightrope between Russia and the West, while expanding partnerships with Türkiye, China, and the Gulf. Kazakhstan’s recent diversification into defense procurement from non-Russian suppliers, its active engagement in energy transition dialogues, and its leading role in regional infrastructure projects make it the clearest example of a middle power in action.

Uzbekistan, with its central geography, large population, and reformist leadership, is emerging as a logistical and diplomatic hub. It has deepened its economic and cultural ties with Türkiye, invested in new transit corridors linking to the South Caucasus, and is a key partner in regional energy and digital projects.

Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan are often seen as peripheral, but their participation in the C5 platform, selective engagement with China and the Gulf, and strategic positioning on issues such as energy transit or labor migration give them niche leverage.

Why Now? Four Structural Shifts

The rise of middle-power behavior in Central Asia is not accidental — it is being driven by at least four structural shifts.

First, the post-Ukraine geopolitical realignment has sharply reduced Russia’s ability to project economic and political influence in the region, prompting Central Asian states to diversify toward the European Union, Türkiye, Gulf countries, South Korea, and Japan.

Second, corridor competition has accelerated. The Middle Corridor (Trans-Caspian International Transport Route) has gained significant traction, providing an alternative to Russian routes for trade between China and Europe. The EU is co-financing key upgrades, including rail links, port terminals, and digital customs systems, though bottlenecks in Azerbaijan and maritime insurance gaps still hamper full operationalization.

Third, platform diplomacy has surged. The C5+1 framework with the United States has expanded into areas such as the Critical Minerals Dialogue, while the EU followed with its own roadmap for raw materials and trade facilitation. China, in response, is offering concessional loans and digital infrastructure.

Fourth, internal reforms — especially in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan — have created political space for more outward-facing, diversified diplomacy, enabling new forms of engagement.

Arenas of Middle-Power Behavior

Central Asia’s assertion of middle-power behavior manifests in several concrete domains. In connectivity and trade, the Middle Corridor has become a flagship initiative. With EU backing under the €10 billion Global Gateway framework, countries have begun pilot projects for customs harmonization, digital waybills, and port modernization — particularly in Kazakhstan and Georgia.

In energy and critical minerals, the EU–Central Asia declaration of intent signed in April laid the groundwork for a roadmap covering uranium, copper, rare earths, and green hydrogen. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are focal points, with European firms exploring long-term offtake agreements and co-investment opportunities. India, which already imports uranium from Kazakhstan, is a natural stakeholder.

Security hedging is another arena. Central Asian countries have participated in military exercises with the US, Türkiye, China, and even India. While formal alliances are avoided, there is a growing appetite for diversifying security relationships, especially in light of instability in Afghanistan and concerns over Russian unpredictability.

Norm-setting and convening power is perhaps the most subtle shift. Central Asian states are increasingly using multilateral forums to position themselves as thought leaders on issues ranging from food security to climate resilience. The hosting of summits with the EU and China in the same year underscores this growing confidence.

Implications for India

India’s interests in Central Asia are manifold and strategic. The region serves as an energy diversification buffer, with uranium, natural gas, and critical minerals aligning with India’s clean energy goals. It is also an essential link in overland connectivity to Europe, complementing maritime routes. India’s engagement has grown via the “Connect Central Asia” policy, investments in the Chabahar port in Iran, participation in the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), and dialogues on rare earths and critical supply chains.

Yet more needs to be done. Rather than launching new corridors, India should fix existing ones by improving border logistics, harmonizing customs protocols, and aligning digital platforms. Integration of Chabahar with the Middle Corridor’s evolving digital standards could create a hybrid route with strategic value.

Further, India must scale up investments in soft power: education partnerships, vocational training, standards harmonization, and joint R&D in energy and technology. These efforts can position India as a long-term partner rather than a transactional player. China and the EU are already deploying capital and forging institutional footholds. Without urgency, India risks being boxed out of key conversations shaping Eurasia’s future.

Risks and Constraints

Despite progress, several challenges could derail the region’s middle-power trajectory. Corridor viability depends on resolving bottlenecks such as cross-border tariffs, opaque customs rules, and unreliable insurance coverage — especially for Caspian Sea segments. Internal political fragility, border disputes (especially between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan), and governance weaknesses could also destabilize gains.

Additionally, great-power pushback is a real threat: Russia still wields coercive influence, particularly through energy dependencies and political elite networks, while China has the economic heft to crowd out smaller players. The EU’s funding models rely heavily on private capital, which may hesitate in the absence of clear guarantees and regulatory clarity. India, if too cautious, could find itself reactive rather than proactive.