Balancing Trade Ambitions and National Security

With new US tariffs threatening Canadian exports, the desire to diversify trading relationships is natural and necessary. But as we pursue closer ties with China and explore new partnerships across Asia, we need to confront some uncomfortable questions about Canada's long-term interests.

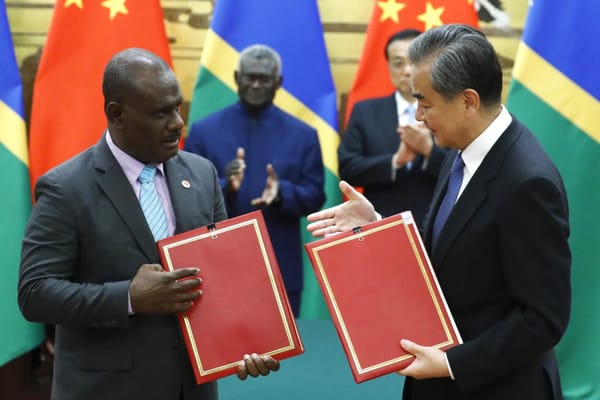

Prime Minister Mark Carney's announcement last week that Canada will double its non-U.S. exports has been framed as a bold declaration of independence from American economic dominance. With President Trump's new tariffs threatening billions in Canadian exports, the desire to diversify our trading relationships is both natural and necessary.

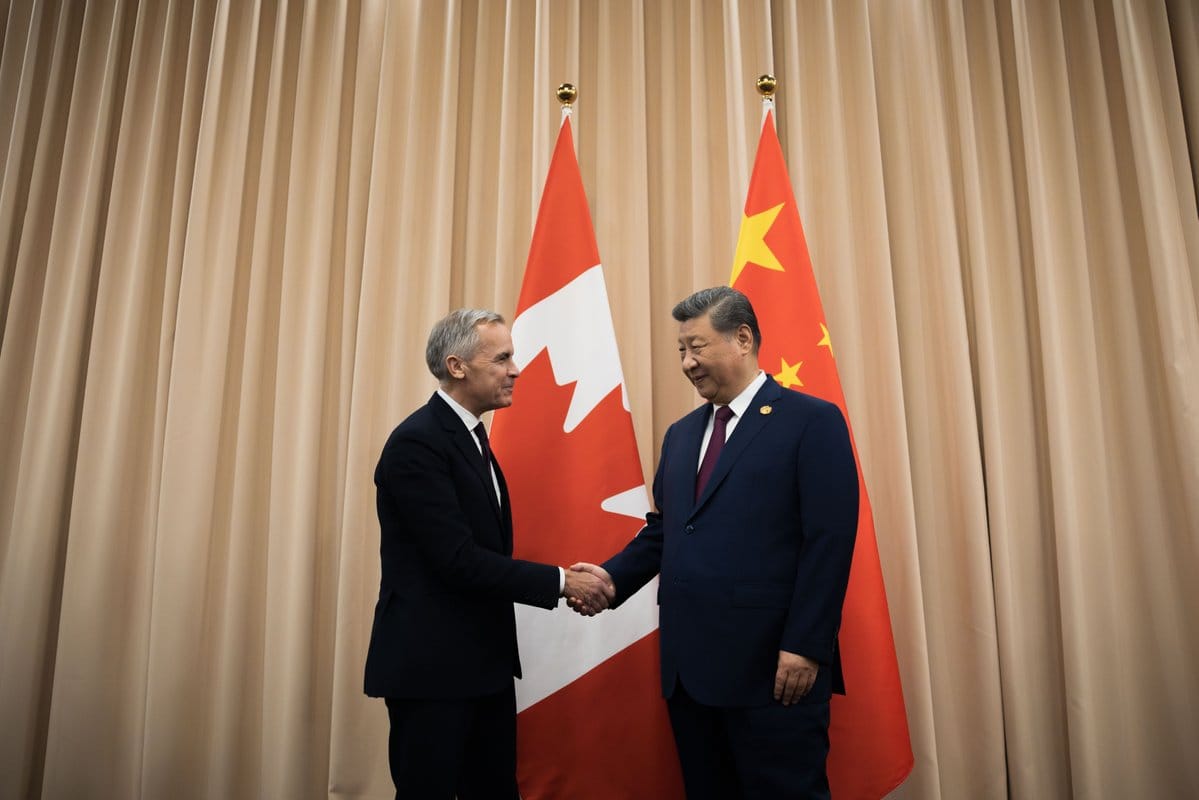

But as we pursue closer ties with China and explore new partnerships across Asia, we need to confront some uncomfortable questions about what kind of diversification actually serves Canada's long-term interests.

A Growing Deficit We Can't Ignore

Let's start with the numbers that should give us pause. In the first half of 2025 alone, Canada's trade deficit with China hit $17.8 billion—a 10 percent jump from the same period in 2024. We're importing Chinese consumer electronics, machinery, and manufactured goods at a far faster rate than we're exporting our minerals and agricultural products to them.

Now imagine we accelerate this relationship as a hedge against American unpredictability. Without careful guardrails, that deficit could widen dramatically. Do we really want to solve our vulnerability to U.S. trade policy by becoming a convenient dumping ground for Chinese manufactured goods? That's not diversification—it's just trading one form of economic dependence for another, potentially a more problematic one.

What Kind of Trade Do We Actually Need?

The real question isn't whether Canada should trade with China or seek new markets. The question is: what kind of economic relationships will make Canada stronger?

Consider what foreign direct investment actually delivers. When multinational companies invest in Canadian operations, the data shows they're 119 percent more productive than purely domestic firms, they pay wages that are 32 percent higher, and they're 147 percent more capital intensive. That's the kind of engagement that builds our industrial capacity, transfers technology and expertise, and creates well-paying jobs.

Compare that to simply importing more finished goods. We get cheaper consumer products, sure, but we sacrifice the opportunity to generate employment for more Canadians and build our own advanced manufacturing capabilities. If Canada is serious about reducing vulnerability, we should be laser-focused on attracting investment that strengthens domestic production—and limiting imports to things we genuinely can't make competitively ourselves.

Looking Beyond the Usual Suspects

There's been much discussion about deepening ties with ASEAN countries, and Prime Minister Carney announced accelerated talks toward a free trade agreement targeting 2026. With 600 million consumers, ASEAN is already our fourth-largest trading partner, yet bilateral trade was just $42.3 billion in 2024, so there's clearly room to grow.

But let's think bigger and more creatively. Canadian companies have already invested $37 billion in African mining operations. What if we expanded that footprint into manufacturing? Production costs in many African countries rival China's, infrastructure is improving, and there's enormous potential for growth.

Canadian firms could bring technology, equipment, and know-how to African manufacturing ventures, creating supply chains that serve not just our market but also the EU, Japan, and other democracies looking to reduce their own China dependence. This isn't charity—it's strategic positioning that could pay dividends for decades.

What About the Security Risks?

In our rush to find alternatives to U.S. trade, are we ignoring security implications?

Canada updated its foreign investment review guidelines in April this year, specifically because of concerns about technology transfer and foreign control of critical infrastructure. We've seen what happens when authoritarian governments gain leverage over democratic countries through economic entanglement.

Before we dramatically expand market access, what screening mechanisms do we have in place? How do we ensure that critical sectors—telecommunications, energy infrastructure, advanced manufacturing — don't become vulnerable to foreign interference or coercion?

These aren't hypothetical concerns. They're questions our allies in Australia, the U.K., and across Europe have already wrestled with, often after painful wake-up calls.

Getting Our Own House in Order

There's something inexplicable about Canada's current situation. On one hand, we're racing to sign trade deals with countries thousands of kilometers away, while on the other, the interprovincial trade barriers still fragment our domestic market. Provincial governments are pursuing their own foreign relationships—some are even entertaining separatist rhetoric—yet we expect to negotiate as a unified country on the world stage. Is this contradiction not obvious enough? What are we doing to address it first?

A fragmented Canada will always be negotiating from a position of weakness, not strength. Before we aggressively expand our global footprint, shouldn't we maximize trade and economic integration among our own provinces? Shouldn't we resolve the internal tensions that make some regions feel they'd be better off going it alone?

The American Question Nobody Wants to Face

This also brings us to the most uncomfortable question of all: what exactly is our alternative to the United States?

The U.S. still receives 75.9 percent of Canadian exports. It's a reality that reflects integrated supply chains built over decades, shared infrastructure, compatible regulations, and a border defended by trust rather than troops.

Yes, American tariffs hurt our economy. We can quantify those costs down to the decimal point. But what we can't easily quantify are the costs of a genuinely hostile relationship with the United States. What would it cost Canada if we needed active military monitoring of our southern border? What happens to our supply chains if trucks face delays and inspections at crossings? What's the economic impact of being frozen out of U.S. defense procurement and technology sharing?

I'm not suggesting Canada should simply accept whatever terms other countries dictate. But we need to be honest about trade-offs. Is accepting some short-term economic pain—even on terms that aren't ideal—actually less risky than rushing into deeper dependencies with countries whose values and interests don't align with ours? That's not a comfortable question, but it's one we should be asking.

What Real Diversification Looks Like

Canada absolutely needs to diversify its economic relationships. But diversification done right means building from a position of strength—strengthening our domestic manufacturing capacity through strategic investment, forging partnerships with democratic countries in Europe and Asia, exploring emerging opportunities in places like Africa, and yes, maintaining pragmatic trade relationships with major economies including China, but only where our interests align.

What it shouldn't mean is reactively substituting one dominant trading partner for another, ignoring security vulnerabilities in our eagerness to spread risk, or pursuing international deals while our own confederation shows cracks.

The path forward requires us to think harder, not just move faster. It demands that we ask tough questions about trade deficits, investment quality, national security, and yes, even whether the relationship we're trying to escape remains more valuable than we want to admit. Canada's prosperity has never come from grand gestures or quick pivots. It's come from a clear-eyed assessment of our interests and patient construction of relationships that serve them.

That's the kind of trade strategy Canada needs now.