A Strategic Corridor in Search of Indian Leadership

India–Iran–Armenia Connectivity Corridor

While India has intermittently acknowledged the strategic importance of linking India to Europe through Iran and the Caucasus, the actual progress on operationalizing the proposed India–Iran–Armenia connectivity corridor has been minimal. Despite multiple rounds of discussion there is little to show in terms of infrastructure investment, trade volumes, or long-term institutional mechanisms.

This stagnation stands in contrast to the region’s evolving geopolitics. As Russia pivots toward Iran, Turkey asserts its influence in the Caucasus, and China deepens its Belt and Road presence, the space for India to shape outcomes is steadily shrinking. The Iran–Armenia corridor remains one of the few overland options that bypass both Pakistan and China, yet it languishes on the margins of India’s strategic priorities.

Historical Context — Old Ties, New Neglect

India’s civilizational engagement with Iran stretches back centuries, through trade, language, poetry, and religious exchanges. Persian was once the language of the Mughal court, and Iranian merchants traversed the Indian subcontinent as easily as they did the Silk Roads. Iran was not just a neighbour in geography but a partner in culture.

Similarly, Armenia, though often overlooked in Indian discourse, played a historical role as a commercial bridge between the Indian subcontinent and Europe. Armenian merchants settled in Surat, Kolkata, and Chennai during the early modern period, forming prosperous communities and even building churches that still stand today.

Despite these connections, India’s recent diplomatic engagement in the region has been reactive at best. As a result, both Iran and the Caucasus have drifted to the periphery of India’s foreign policy vision.

The Present Moment — Chabahar, INSTC, and Geopolitics

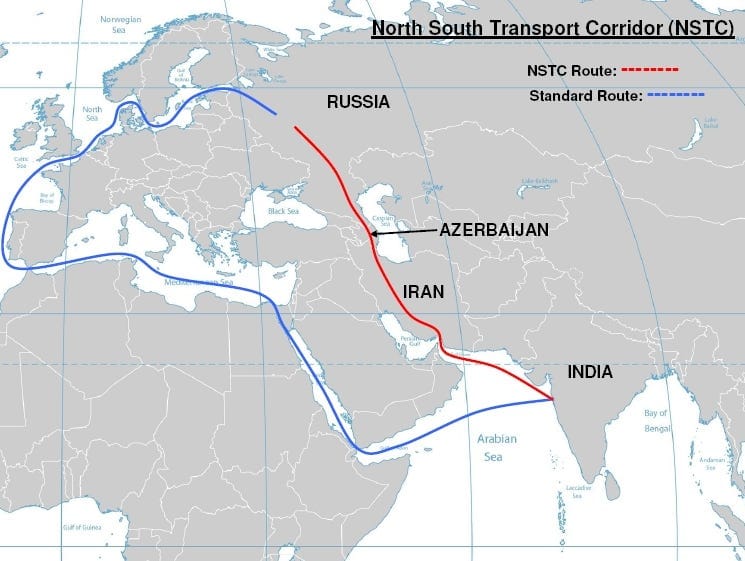

India’s involvement in Chabahar port in southeastern Iran is often cited as a counter to China-backed Gwadar port in Pakistan. Chabahar is also a vital node in the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), an ambitious project that seeks to connect India to Russia and Europe via Iran, the Caspian Sea, and the Caucasus.

Armenia has emerged as a key player in the “Middle Corridor” that complements the INSTC. This corridor links India and Iran with Europe via Armenia and Georgia, bypassing both Turkey and Russia. For India, this is not just about trade — it is about creating strategic options in a world where chokepoints like the Suez Canal or tensions in the South China Sea can quickly disrupt global supply chains.

At the same time, regional dynamics are shifting rapidly. Russia, isolated by Western sanctions, has grown closer to Iran. China continues to dominate infrastructure financing across Eurasia through the Belt and Road Initiative. Turkey has become increasingly assertive, backing Azerbaijan in the Armenia conflict and strengthening ties with Pakistan.

India is present in this theatre, but it is not driving the agenda.

Why This Matters for India — Strategic, Not Symbolic

For India, the stakes are too high to remain on the sidelines. India’s long-term energy security continues to hinge on access to diverse and stable suppliers. Despite being under Western sanctions, Iran remains one of the world’s largest holders of oil and gas reserves.

On the trade and connectivity front, Chabahar port and INSTC represent a viable alternative to the congested and geopolitically vulnerable Suez Canal route. These routes could offer Indian exporters faster and cheaper access to European markets, giving India greater logistical flexibility and commercial competitiveness in an increasingly fragmented global trading environment.

Beyond economics, this corridor has clear geopolitical value. Armenia, though small, can play a strategic role in the Caucasus, especially as Turkey, Pakistan, and Azerbaijan are tightening their trilateral coordination. India’s engagement with Armenia can act as a subtle but meaningful counterweight to this emerging axis, enhancing its own influence in a region where multiple power blocs are competing for space.

Finally, this corridor deserves recognition as part of India’s broader West Asia strategy. While the Gulf receives most of the attention due to labour flows and oil dependence, the Iran–Caucasus route offers India a land-based gateway into the Caspian, Black Sea, and Central Asia. It is not merely a trade route, but a geopolitical artery that could shape India’s continental presence for decades to come.

The Missed Opportunities — And Risks of Inaction

India has been hesitant to commit fully to Chabahar. This cautious approach allowed China to strengthen its footprint in Iran through infrastructure investments and long-term oil deals.

The INSTC remains underutilised. While the corridor was conceived more than two decades ago, the volume of cargo that actually travels along it is minimal. Bureaucratic inertia, lack of marketing, and fragmented implementation have kept it from becoming a viable alternative to other global trade routes.

But inaction comes at a price. If India does not invest political and economic capital in this corridor, it will lose leverage in a region that is becoming central to Eurasian connectivity. As new routes are finalised and infrastructure is laid, India risks being marginalised from a corridor that could define the next phase of global trade.

One core reason for this oversight is what could be termed India’s “maritime bias.” New Delhi’s strategic vision is disproportionately focused on the Indian Ocean and the Indo-Pacific, often at the expense of continental Eurasia. But great powers cannot afford such geographic myopia.

The Way Forward — What India Could Do

If India is serious about being a continental as well as a maritime power, it must recalibrate its approach.

First, treat Chabahar and the INSTC not as optional side projects, but as strategic imperatives. This means funding, high-level diplomatic attention, and timelines for implementation.

Second, institutionalize a trilateral framework with Iran and Armenia. Regular dialog, shared investment mechanisms, and a formal working group on connectivity could prevent ad-hocism and create momentum.

Finally, balance East and West. Engagement with the US and EU need not preclude deepening ties with Eurasia. In fact, leveraging Iran’s location and Armenia’s European proximity could enhance India’s bargaining position with both BRICS and Western blocs.

Conclusion

India’s ambitions to be a global power cannot rest solely on Indo-Pacific partnerships or symbolic summits. They require concrete, sustained investment in regions that lie between oceans and continents. The Iran-Armenia corridor offers a rare chance to bridge India’s maritime strengths with continental reach.

This is no longer just about Chabahar or a set of cargo trains across the Caucasus. It is about whether India reclaims its historical place as a connector of worlds — from the Indian Ocean to the Eurasian heartland. If it misses this window, the corridor may still be built. But India may find itself waiting at a gate where the rules have already been written by others.